What Happens to Your Body When You Skip Meals?

Introduction

Are skipped meals harmless, a metabolic shortcut, or a hidden health risk? In today’s fast-paced world, meal skipping either by choice or due to busy routines is more common than ever. Whether it's a structured approach like intermittent fasting (IF) or an unplanned occurrence, omitting meals can significantly affect your metabolism, mood, and long-term health. While some believe it's a pathway to better health, studies present a complex picture. Research has shown that skipping meals can influence blood sugar control, appetite hormones, and energy balance though findings often vary, making it difficult to determine universal outcomes.

More studies are needed to understand how occasional vs. habitual meal omission affects food choices, diet quality, and metabolic risk. Understanding these effects can help clinicians provide better guidance for weight management and overall health.

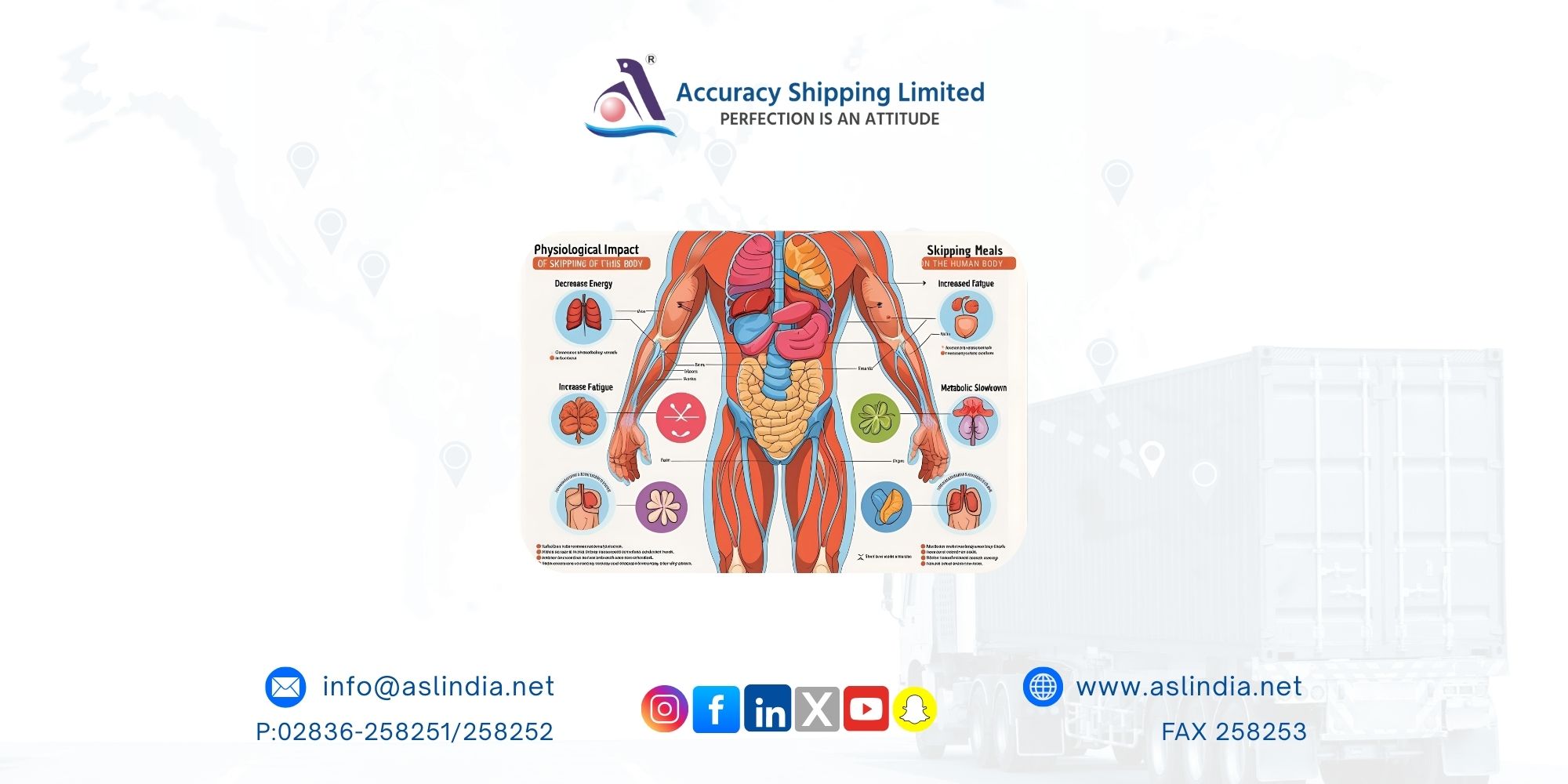

Physiological Response to Meal Skipping

When you skip a meal, your blood glucose and insulin levels drop. This signals your pancreas to release glucagon, a hormone that stimulates the liver to convert stored glycogen into glucose. Once glycogen reserves are depleted, your body turns to fat for energy. Triglycerides from fat cells are broken down, and the liver produces ketone bodies to fuel the brain.

Meanwhile, leptin a hormone that suppresses hunger declines, and cortisol (the stress hormone) increases. Ghrelin, known as the “hunger hormone,” rises, boosting your appetite and prompting the body to prepare for future food shortages by conserving energy and increasing fat breakdown.

Cognitive and Behavioral Effects

Skipping meals doesn’t just affect your body it impacts your brain, too. People who regularly skip meals may experience short-term cognitive impairments such as reduced attention span, weaker memory, and difficulty planning. Studies in animals mirror these findings, revealing increased aggression and behavioral shifts due to intermittent access to high-sugar or high-fat diets.

Prolonged energy restriction can heighten cravings for palatable foods, disrupt normal hunger responses, and lead to compulsive eating once food becomes available. This overcompensation often results in binge-eating episodes and fluctuating moods, placing both mental and metabolic health at risk.

Impact on Metabolic Health

The timing and frequency of meals play a key role in maintaining a healthy metabolism. Eating one or two structured meals daily may reduce BMI and support weight loss, especially when accompanied by longer overnight fasting. However, irregular patterns like skipping breakfast and overeating at night can lead to fat accumulation and poor insulin response.

Morning meals align better with our biological rhythms. Insulin sensitivity is naturally higher in the morning, helping regulate blood sugar more efficiently. Frequent, smaller meals may help lower cholesterol and maintain metabolic stability but only when they're balanced and not used to replace nutrient-dense meals.

Skipping Meals vs. Intermittent Fasting

It’s important to distinguish between random meal skipping and intentional intermittent fasting (IF). IF includes structured approaches like:

Time-Restricted Eating (TRE): Limiting food intake to a 4–10-hour window during the day.

Alternate-Day Fasting (ADF): Alternating between normal eating days and fasting or low-calorie days.

Both methods can promote weight loss, reduce fat mass, and improve lipid and glucose markers but not dramatically more than standard calorie restriction. In contrast, habitual meal skipping (especially breakfast) is associated with increased risks of type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

Individual Variability and Risk Factors

Your age, sex, and daily habits influence how your body reacts to skipped meals. Children and older adults tend to eat earlier, while teens and younger adults often eat later. Disrupting these natural patterns can desynchronize internal body clocks, impair glucose metabolism, and reduce fat clearance especially with late-night eating.

Cultural and socioeconomic factors also matter. For example, lower-income adolescents often snack more frequently and gain more weight over time. Regional eating habits differ too: Mediterranean populations generally eat earlier and healthier, while Northern Europeans consume more late-day calories.

Clinical and Public Health Implications

Structured eating patterns, especially breakfast consumption, are linked to better overall nutrition. A Korean study found that regular breakfast eaters consumed more fiber, calcium, and potassium and had a more balanced diet. In contrast, skipping breakfast led to lower energy intake and reduced triglyceride levels but at the cost of micronutrient deficiencies.

In fact, 91% of habitual meal skippers fail to meet calcium requirements, while 73% and 98% lack sufficient vitamin C and folate, respectively. Over time, these deficiencies can lead to serious health issues. Additionally, skipped meals may trigger disordered eating behaviors, as people compensate later with large, energy-dense meals.

Conclusion

Skipping meals can have wide-ranging effects from blood sugar fluctuations and increased cortisol to behavioral changes and poor nutritional intake. While structured approaches like intermittent fasting may offer benefits, unplanned or frequent meal skipping carries risks. Individual responses vary, so it’s vital to consider age, lifestyle, and cultural context when evaluating the practice.

Ultimately, consistency, balance, and proper meal timing are key to maintaining optimal metabolic, mental, and nutritional health.